We have returned from our hiatus as of mid-august as expected!! check back frequently for updates!!

If you are using a mobile browser, please ensure you change your settings to display the desktop site for the time being!!

From Research Chemicals to Recognized Therapies: The Case for Legal Reform

In the early 2000s the landscape of psychoactive substances was changing rapidly, with new molecules—slightly modified versions of older hallucinogens, stimulants, or “empathogens” (drugs which increase feelings of empathy and enhance sociableness)—becoming increasingly available to ordinary people via the internet. Often called “research chemicals,” “designer drugs,” or “grey market drugs,” these substances occupied a legally ambiguous space that in many ways led both to serious harm and to lost opportunities for medical science. This article traces how the scene developed around the turn of the century, when internet use became widespread: what substances were involved, who was distributing them, how the law responded (sometimes poorly), how things shifted, and how we might do better going forward.

9/19/20256 min read

Early Players & Substances: 2C, 2C-T, and Analogues

Some of the best-known early research chemicals came from the 2C series (a group of substances belonging to the phenethylamine family) as well as from the tryptamine family. The “2C” refers to two carbon atoms between the amine group and the aromatic ring. Variants like 2C-I, 2C-E, 2C-T-2, 2C-T-7, and 2C-T-21 differed by substitutions on the ring (halogens, methoxy groups, thio groups, propylthio etc.). These small structural changes could significantly alter potency, duration, toxicity, and subjective effects. These concepts are similarly applied in research and development of pharmaceuticals, but more will be discussed on those type of similarities later.

2C-I: a psychedelic with prominent visual and emotional effects, popularized by Alexander Shulgin (as was the concept of developing such compounds for human research.)

2C-E: more intense, longer lasting, and more challenging in terms of dose control.

2C-T-7 (“Blue Mystic”): a thio-substituted analogue associated with several deaths, especially when insufflated.

2C-T-21: less well studied, but tragically implicated in the death of 22-year-old James Edwards Downs in Louisiana after purchasing it online.

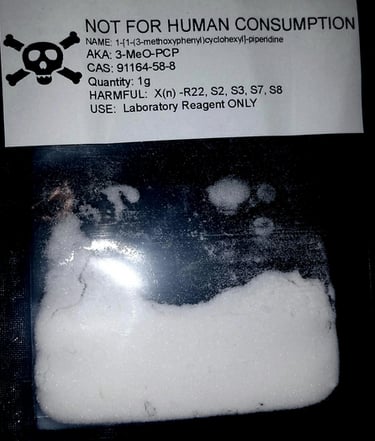

These substances were often sold under labels such as “not for human consumption” or “for research purposes only.” Vendors leaned on these disclaimers to dodge legal accountability under analogue laws, even as forums and communities were openly trading dosage advice and trip reports.

Michael Burton & Operation Web Tryp

One of the more infamous names in this era was Michael Burton, who ran American Chemical Supply. Alongside several other online vendors, Burton was indicted in Operation Web Tryp, a U.S. DEA investigation that culminated in July 2004.

Operation Web Tryp targeted five websites and ten individuals accused of distributing unscheduled psychoactive chemicals like 2C-I, 2C-T-7, and 5-MeO-DiPT. The investigation followed multiple overdose cases, including the death of James Edwards Downs which resulted from accidental over-consumption of 2C-T-21 purchased online.

The case highlighted the fragility of the “for research purposes only” disclaimers and established that vendors could still be prosecuted under the Federal Analogue Act if intent for human consumption could be demonstrated.

The Analog Act & Its Limits

The Federal Analogue Act (1986) allows the U.S. government to treat a substance as Schedule I if it is “substantially similar” to an existing Schedule I or II drug and intended for human consumption.

To evade this, vendors would:

1.) Sell compounds in bags labeled “not for human consumption.”

2.) Advertise vague “research” uses.

3.) Avoid dosing instructions in sales copy, while forums spread the real information.

Operation Web Tryp showed that when marketing, customer communications, and real-world outcomes (like overdoses) were considered together, the analogue law could be applied effectively. But the Act’s ambiguity ultimately created years of uncertainty, during which dangerous substances circulated freely.

From 2C Compounds to NBOMe, NBOH, MXE, and “Bath Salts”

Once 2C-series phenethylamines and early tryptamines were scheduled, the underground scene adapted. New chemical families began appearing:

NBOMe and NBOH derivatives — such as 25I-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, and their NBOH counterparts. These were ultra-potent psychedelics active at microgram levels. Overdoses were common, often fatal, because the difference between a threshold and a dangerous dose could be measured in grains of dust.

MXE (Methoxetamine) — a dissociative related to ketamine, but with a longer duration. Many users claimed it had therapeutic qualities for depression and anxiety, though cases of dependence and psychiatric complications also emerged.

Substituted cathinones (“bath salts”) — stimulants like mephedrone, MDPV, and α-PVP surged in popularity. They were cheap, euphoric, but carried risks of addiction, psychosis, cardiovascular strain, and erratic behavior.

Other stimulants and phenethylamines such as 2-FA (2-fluoroamphetamine) offered slightly altered profiles of established drugs but still fell quickly into legal crosshairs.

Each wave followed the same cycle: online hype, rapid uptake, hospitalizations and fatalities, and then swift emergency scheduling.

Medicinal Potential vs. Schedule I Roadblocks

Despite the harms, users and researchers repeatedly noted therapeutic potential:

MXE was described by many as anxiolytic and antidepressant similar in nature to ketamine, but with enhanced therapeutic potential.

Classic psychedelics (LSD, psilocybin, DMT) are now being validated in clinical trials for depression, PTSD, and end-of-life distress.

5-MeO-MiPT (a so called “research chemical” that has gained some popularity in illicit markets) has even been highlighted by AI-driven analysis of user reports as a promising therapeutic candidate, and it has avoided scheduling so far—an increasingly rare exception considering many other similar substances have been met with the fate of becoming Schedule I promptly once popularized.

The problem is that nearly every time a new compound gains attention, the DEA emergency schedules it into Schedule I. By law, Schedule I substances are defined as having “no accepted medical use,” creating a catch-22 where medical research is nearly impossible because the drug is Schedule I, and it remains Schedule I because there is no medical research.

Linder’s Case: An Echo of a Better Idea

This tension even surfaced in federal courts. In Linder v. Milgram (7th Cir. 2022), David Linder challenged his conviction for distributing unscheduled tryptamines (AMT and 5-MeO-DiPT). One of his arguments was that under 21 U.S.C. § 811(h), the DEA should not have the power to emergency-schedule substances into Schedule I.

Linder pointed to legislative history suggesting Congress envisioned temporary scheduling into Schedule III, where drugs with potential medical use can be studied more readily. While the Seventh Circuit ultimately rejected his claim—holding that the statute clearly allows temporary placement into Schedule I—the very fact that such an argument arose highlights a long-standing tension: should emergency scheduling always mean the harshest, most restrictive category, or should there be room for a research-friendly middle ground?

A Better Model: Dual-Class Scheduling

At Rise Above The Risk, we believe it’s time for a smarter approach:

Create a dual-class framework, similar in nature to how GHB is to be considered Schedule I when it is in its illicit form (or being diverted for illicit use) but Schedule III when prescribed.

Place NPS compounds in Schedule I for illicit purposes, but allow a Schedule III research track for accredited scientists.

This would let law enforcement crack down on reckless vendors while giving legitimate researchers access to study compounds with therapeutic promise. Once substantial enough research has been done, there may even be possibility of regulated sales for what could be considered "recreational use" as well considering the fact that allowing for such would theoretically reduce the impact of the risks that are posed by unregulated markets. But, that is a topic of discussion I will save for another article entirely.

This model not only mirrors Linder’s line of argument but also offers a practical fix for the research deadlock created by Schedule I. In other words: punish reckless distribution, but don’t lock the door on science. The framework for this approach already exists, and it wouldn’t take much other than the simple passing of a bill to allow for a similar approach to be applied to how Novel Psychoactive Substances are scheduled in the US. The thing is though, that there is relatively little public interest in getting such a bill passed at this time as even psychedelic research is in its infancy, and the vast majority of people have no vested interest in such. To change this would require finding a means of raising public awareness of the situation in hopes that it might spur some sort of legislative action.

Why Reform Matters

The history of research chemicals shows two things clearly:

1.) Unregulated grey-market sales lead to real harms—overdoses, deaths, hospitalizations.

2.) Blanket Schedule I bans choke off medical research that could prevent those harms and unlock life-changing therapies.

Without going into elaborate detail, we now have substantial evidence that psychedelics and related substances can be powerful medicines. Clinging to outdated “war on drugs” frameworks from the 1970s only repeats the mistakes of the past.

The future could look different: open scientific inquiry, harm-reduction-first policies, and treatments for conditions like depression, PTSD, and addiction that current medicines fail to address. But only if we fix the system. This change has to start with those of us who are in the know, and it is our job to educate others as best as possible whenever appropriate.

Conclusion

The rise and fall of early 2000s research chemicals was chaotic, tragic, and instructive. It showed how fragile the line is between exploration and exploitation, between medicine and misuse. But it also showed us the cost of bad laws: when every new compound is automatically treated as contraband, society loses not only lives to reckless markets, but also cures locked behind red tape.

It’s time for society to rise above these risks. By building a system that punishes reckless distribution while empowering legitimate research, we can finally move beyond the mistakes of the past—and toward a future where innovation and safety go hand in hand.

Links to Outside Resources for Additional Information Regarding "Research Chemicals" and Other Related Insight

Operation Web Tryp — Wikipedia

Erowid Article on 2C-T-21 (James Edwards Downs case) — Erowid

Federal Analogue Act — Wikipedia

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Current Evidence — review articles (background on therapeutic potential, psilocybin, etc.)

Washington Post – FDA gives an early nod to psychedelic research (re: 5-MeO-MiPT being selected for study)

Bad Trip for Online Drug Peddlers — Wired

Operation Web Tryp — Wikidoc page (mirroring Wikipedia content) outlines which sites were involved, which individuals were arrested, deaths claimed, non-fatal overdoses, etc.

DEA Announces Arrests of Website Operators Selling Illegal Designer Drugs — national release announcing the culmination of Operation Web Tryp (mirror of the original DEA page)

U.S. Arrests Internet Merchants of Designer Drugs — DEA New York Division release with arrest details tied to the SDNY complaint (names, locations)